According to Google Earth, my house is 15,968.78 kilometres from the Metropolitan Opera New York, so it isn't practical to go there as often as I would like. I would have liked to have seen the recent production of Nixon in China, a marvellous work and a turning point in the development of modern opera. At least these days we have internet streaming and the live HD broadcast's to cinemas, although here they are not live, probably because few of us, no matter how good our intentions, would be there at 5 am of a Sunday morning. So we saw a recording two weeks after the Saturday matinee which was telecast. Good as these transmissions are, it is quite a different experience from being there.

The music is remarkable and memorable. There may be exceptions, but I think there should be music in opera which engages us as we listen; and which we can remember later on. I was pleased to see this thought echoed in Michael Tanner's article in The Spectator about the recent premier of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s new opera, Anna Nicole. He said that ...one of the cardinal musical weaknesses of the piece (is) that it sends one out of the theatre with nothing musical going on in one’s head. When I first saw John Adams' Doctor Atomic in 2005, I had the impression it was a work that would last for this very reason. The powerful aria Batter my Heart, and Am I in Your Light, were not only engaging at the time but, remarkably for a piece newly heard, remained with me long after.

In Nixon we have the thrilling soprano aria I am the Wife of Mao Tse-tung, a little of the music more developed in Adams' orchestra piece The Chairman Dances and the pastiche which satirises the revolutionary vogue for group composition accompanying the revolutionary ballet.

We also have the RN's long aria News ... has a kind of mystery, which is an example of the sympathetic way in which the libretto and the music treat him. The other example is his monologue in the third act about his experiences in the second world war. Nixon's character is carefully developed to avoid the stereotype Watergate villain. Speaking at an event webcast on WQXR/Q2, John Adams said that at the time the opera was written all most people saw of Nixon was a succession of comic mimics on late night television.

On the same webcast, Peter Sellars saw the writing of an opera about recent historical events in a various ways. He said that the usual television commentary made a snap judgement and then moved on; it presented historical events inconsequentially so that we don't have the same feeling about the significance of historical events as we have about the history of past centuries. Music and poetry can lift you past the facts into a visionary space which offers us something much more profound.

He also saw Nixon as an instance of what opera can do: we go to a place that was never announced at the beginning . He saw this as a place for secret thoughts, a place you don't have words for, which creates feelings which none of us know how to process.

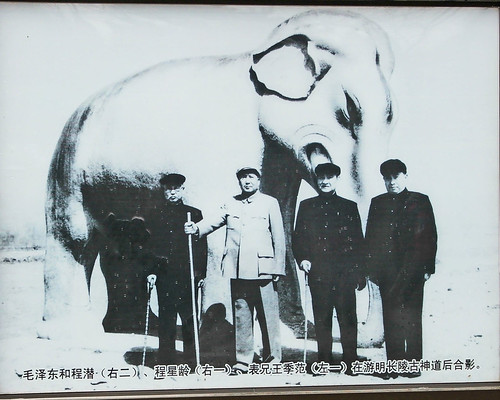

I think this gives us a good idea where we are headed in Nixon. The opera begins in a documentary way, depicting the arrival of the Nixons in Beijing and the his meeting with Mao. It then veers off into a surreal landscape inspired by a performance of the revolutionary ballet The Red Detachment of Women, in which Henry Kissinger somehow becomes a sadistic landlord and Pat Nixon intervenes in the action to save his victim. The last act consists of monologues by Nixon, Chou En Lai and Mao in which they provide a historical context which, up to that point, was missing, and an imagining of what was going on inside their heads.

Of course we have no idea what was going on inside their heads. History books which invent dialog are often and rightly condemned. Opera is not a history book; and one of the things it can do is create a world which simulates the kind of thoughts we have when thinking about past events. I don't think when we read history we always convert the story into a catalogue of established facts; we do the opposite. We imagine what it would have been like to be a Nixon or a revolutionary in China, and the opera give a voice to such thoughts and feelings, just as opera gives a voice to the thoughts and feelings of a Tosca or a Violetta.

Max Frankel, a journalist who covered Nixon’s trip to China, does not accept this. In an article in the New York Times, he argues that operas shouldn't be based on contemporary events. He is not very convincing. The article suggests that Verdi and Shakespeare wrote of long past events for aesthetic reasons, overlooking the political censorship which constrained both of them. He concludes:

It is easy to mock the story lines of most operas, but that is not my main purpose here. I mean to suggest, in all sympathy, that when living reality is so blatantly harnessed to bait the audience with familiarity and to create a heightened sense of excitement, it risks being constrained by that same reality from reaching true depths of drama and character. At the sudden and surprisingly ambiguous end of “Nixon in China” we hear Chou’s plaintive aria asking, “How much of what we did was good?/Everything seems to move beyond/Our remedy.”

I left wondering whether the opera’s creators might not share his anxiety.

I would like to ask him: why shouldn't familiarity be an element in a work of art? and doesn't any heightened sense of excitement achieve exactly what Peter Sellars set out to do - remove the events from the babble of the daily news and suggest their real significance. And what are the "true depths" of drama and character? The drama and character in Nixon are absorbing and creative. Surely nobody would mistake an opera for an attempt at an all encompassing and definitive historical narrative, even if it was possible to produce one.

Nixon is sung by James Maddalana who created the role in 1987. He also sings on the recording made at that time with the Orchestra of St. Luke's and Edo de Waart on which his youthful voice sounds a little out of character. He is now more of an age with the Nixon he portrays. When I heard the internet stream of the opening night, and a stream of the performance seen in the movie theatre, I wondered why he was allowed to continue. His voice was breaking up and he sometimes coughed. The reviews were surprisingly favourable,and seeing his performance in the cinema showed why this was. It's certainly not great singing, but he inhabits the part so well that this doesn't seem to matter. He doesn't look much like Nixon, but very soon he becomes Nixon.

The other highlight of a uniformly excellent performance was Kathleen Kim's portrayal of Chiang Ch'ing. The aria I am the Wife of Mao Tse-tung was thrilling, and a complete answer to those who would not see recent history on the operatic stage. It might be a stereotype but in both the aria and her performance of it were a memorable depiction of a fanatical revolutionary woman.

Henry Kissinger was sung by Richard Paul Fink. He was excellent in a difficult role. My one reservation about Nixon in China is the way in which it portrays Kissinger as a pantomime villain, in contrast to its empathy with all the other characters. Doctor Atomic did something similar by making General Groves, the military head of the Trinity project, very unfairly, a kind of buffoon. Perhaps there is thought to be a need to offset the serious plot with some comic relief. An itinerant scholar suggested to me that this was a tradition of American musical theatre: cf. and cp. Officer Krupke in West Side Story. If so, I am not convinced it's a tradition that should have been followed here.

No comments:

Post a Comment