I took this photo while walking around in May. I was attracted by the contrast between the new buildings and the church. I didn't know the name of the church; and when I was back in Sydney posting photos to Flickr it took me some time navigating around on Google Earth to identify the building. I found it was St. Stephen Walbrook one of the many churches designed by Christopher Wren (1632 – 1723) after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

So I returned for a closer look in November. I found that the building and its history provided some fascinating insights into the way we appreciate historical structures and monuments. What is the significance of an old or ancient monument; what is a "Wren church"; and how important is it that old buildings are kept as they were when built ?

There is said to have been a church on the site since at least 1090 when Walbrook was a stream flowing into the Thames. The one destroyed by the Great Fire was built in 1428 by which time the stream had gone and Walbrook was a street. Construction of the Wren church began in 1672 and was completed, except for the spire, by 1679. It is one of the hundred or so churches in the City of London, many of which were destroyed by the Great Fire and rebuilt to designs by Christopher Wren or his office.

The spire was added 1713-15. It may have been designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The whimsically elaborate design has a lot in common with his work.

There is a general history in a leaflet available for download on the church's website.

From the outside the church could hardly be called impressive:

Like St. Mary Woolnoth, a short distance away, it shares its site with a Starbucks shop. This is not as strange as it seems, like many other City churches, the building has never been free standing and in the past has been more obscured by surrounding houses, shops and offices than it is at present.

Once inside things are very different:

we find a space well lit by from large plain glass windows, with attractive bench pews around a central altar, sculpted by Henry Moore. The altar and the circles of pews are very modern. The original interior had a different pattern.

In the seventeenth century Church of England, instruction was more important than ritual and churches were designed for the preaching of sermons. Wren designed St. Stephen as an auditory. The pulpit was the focus, and the body of the church was designed to enable the whole congregation to see and hear the preacher.

The original wine glass pulpit and altar have survived war and restoration and are still there:

but the pulpit no longer dominates the church.

This engraving from early in the nineteenth century shows the box pews for which the church was designed. At time the engraving was made the large east window was occupied by an altarpiece The Burial of St. Stephen by Benjamin West R.A. (1738 – 1820) While Wren did not design the box pews, it can be seen that the columns have very high bases designed to accommodate them.

Various repairs were made in the first half of the nineteenth century and in 1850 The Burial of St.Stephen was moved to the north wall, and the windows filled with Victorian stained glass. In 1886-7 substantial remodelling took place. The box pews were taken out and replaced with movable seats, and the original paving stones were replaced with a mosaic floor. The octagonal pedestals of the columns, as seen in the engraving above, were replaced with the square ones seen today. It is unclear whether or not this change restored them to their original form.

The church was not hit by high explosive bombs during the Nazi air raids of the Second World War; but the structure was damaged by a land mine and incendiary bombs damaged the part of the dome which fell in flames into the body of the church. Seats and choir stalls installed in 1887 were lost to the fire, but not the wine glass pulpit. The Victorian stained glass windows were destroyed.

The church was repaired after the war and re-opened in 1953. In 1963, new stained glass windows by Keith New were installed.

A photograph of the interior in Wren by Margaret Whinney (1971) shows the altar on the east wall and the pulpit, with rows of open backed pews and chairs in front of them. The window above the altar and the two smaller windows on each side are filled with the new stained glass.

Meanwhile, excavations for large buildings in the surrounding area had altered the level of the water table, and the flow in the now underground Walbrook was reduced. The ground under the church, dried out and the building became unstable. Further substantial works were required.

Very substantial structural alterations were done to provide support for the dome. The floor was rebuilt in steel and concrete and the mosaic floor replaced with stone paving. The altar by Henry Moore was installed during these works, but not without controversy. Alterations of this kind require the approval of church courts: and installation of the new altar was refused by the London Consistory Court on the grounds that the altar was not a table as required by church doctrine; and that in any event it was unsuitable and incompatible with Wren's design. This first issue, which goes back to the replacement of altars with communion tables as part of the protestant reforms of Edward VII, doesn't directly affect the issues of authenticity and aesthetics which interest me, but it did result in an appeal being heard by the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved as the case involved questions of doctrine, ritual or ceremonial. This court constituted by Two High Court judges and three bishops, allowed an appeal and the altar, which had been installed in the course of renovations, remained.

The doctrinal question turned on whether something without legs could be a table, which at least in argument led to a discussion of "the quality of tableness". I would be happy to leave this to the ecclesiastics were it not for the facts that the "table" is a cylindrical piece of marble 3'5" in height and 8' in diameter weighing 10 tons, which looks to me more like a sacrificial altar than anything I have ever seen in a church.

When I was in the church, I found it had the same uplifting feeling of openness and light which I have experienced in other English churches of the period with clear glass, for example, Hawksmoor's St. George's Bloomsbury. I was not aware at the time of the controversy about the interior as we see it now.

London Consistory Court held that the issue turned on the departure from Wren's intention. I learned that architects talk of "reading a building". So in this case, entering from the west door with the box pews in place, one was faced with a church of the expected longitudinal, nave and aisle pattern. But as you moved forward and saw the dome above another "reading" of the building became possible. The interior was deliberately ambiguous. By placing a circular altar and surrounds under the dome, the present arrangement breaks the tension between the two aspects of the design. I imagine this would be seen as wrong by those who believe that preserved buildings should be, as far as possible, in their original state. It is not possible now to experience the spacial ambiguity in the same way.

In allowing the appeal, the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved rejected the notion that there was an objective test to be applied. Departure from Wren's perceived intention could not be "wrong"; it was all a matter of personal taste. There were a number of experts in art and design who liked the new proposal, and the appeal court held that this weighed strongly in its favour.

The new arrangements were said to have great artistic merit and to be in harmony with the building notwithstanding the loss of some of the force of the original design. I think the experts and the members of the court were very much influenced by the reputation and standing of Henry Moore at the time. Of course, all art is constantly being re assessed; and I gained the impression in watching Alastair Sooke's TV program Romancing the Stone, that Moore's reputation has entered an eclipse. The reclining figures, recognisably his work, which can be seen in many galleries and public places around the world were described as "British Council art". I took this to mean stylish but anodyne objects which could be safely exported as bits of official culture.

I will need to have another look at the church with all this in mind. However, I think it may well be that the altar and its surrounds will be viewed in the same light as the stained glass, installed when it was in fashion and now removed. But I suspect that if box pews were installed in its place they would rarely be occupied.

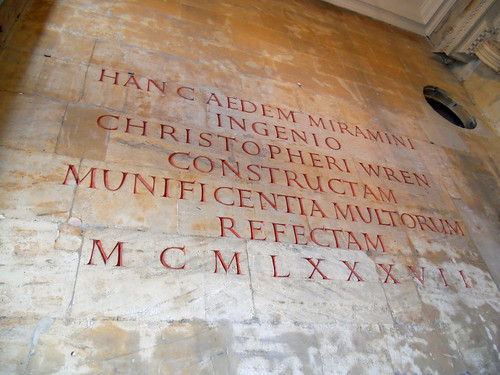

When the most recent alterations to the church were completed this inscription was placed at the entrance:

A true reading? Maybe, with a new ambiguity.

No comments:

Post a Comment