Last

July, I went to an early evening concert given by Ben Johnson, tenor and James

Baillieu, piano at St. Giles Cripplegate.

It was called Postcards from Paris and comprised songs by Poulenc,

Faure, Duparc, Hahn and Lennox Berkeley.

Berkeley was not French but, if I need mention, studied with Nadia Boulanger and spent some time in Paris.

It was a delightful concert which introduced

me to lots of unfamiliar music which I will continue to explore. Before the concert I looked around the church

and found several things of great interest one of which led me to Waseda University

in Japan.

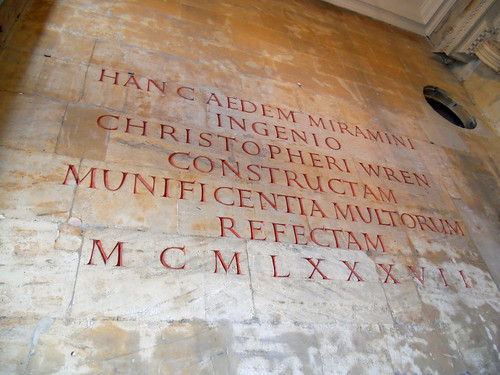

St.

Giles Cripplegate (as it was built outside the city walls actually St.Giles

without Cripplegate), now surrounded by the Barbican redevelopment, is a

medieval church which dates from the 12th century. It was

completely rebuilt in 1390. There was a

fire in 1545:

The xii day

of September at iiii of cloke in the mornynge was sent Gylles church at Creppyl

gatte burnyd, alle hole save the walles, stepull, belles and alle, and how it

came God knoweth.

Following

the fire there was another rebuilding, though some of the 14th century

fabric survives in the walls and base of the tower.

The

red brick section of the tower with pinnacles was added in the 17th

century. The cupola above it was added

as part of postwar restoration, though one of similar design appears in a

picture of the church from 1830.

The

church is situated to the north of the area devastated by the Great Fire of London

in 1666 and was unaffected by it; maps

of the area overwhelmed by the fire, indicate that the city wall close to St.

Giles acted as a firebreak.

There

was further restoration both before and after damage caused by the Cripplegate

fire of 1897. But worse was to come. Only the shell of the building survived enemy

bombing raids in 1940 in which almost all the furnishings were destroyed as

well. The church has published a picturegallery * showing the building before and after this catastrophe.

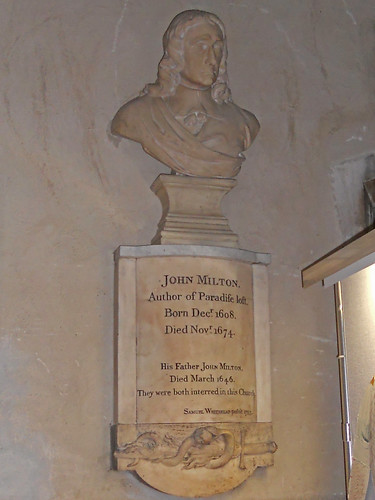

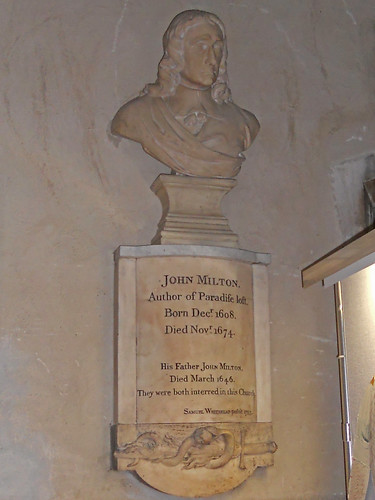

John

Milton (1608 - 1674), who lived nearby for most of his life was buried in the

church.

Sometime

later, in 1793, a bust by John Bacon the elder was installed. Paradise Lost is remembered in the carving

under the pedestal.

Bacon

has been called the first great sculptor of the industrial revolution. He established a factory-like studio with a

large output. In 1771 The Daily Advertiser stated that

(Bacon’s) merit as an artist was too well

known to need any encomiums.

Milton

does not look at his best in my photograph of the bust. This may be because the picture was taken

with an unsophisticated camera using a basic flash, or because Bacon was no

republican. When invasion from

revolutionary France threatened, he provided his apprentices with weapons and

subjected them to military drill. He

berated a clergyman for mentioning equality.

In

1903 this memorial was joined by a statue of the poet. (The bust to the left in

this photo is of John Speed (1552 – 1629), “Citizen

and Merchant Taylor” who is also buried in the church.) I read that the statue of Milton was added as

part of a campaign to drum up interest in St.Giles during a fund raising drive.

When

I visited, Milton had been provided with a copy of the Penguin edition of

Paradise Lost; and other photos on Flickr show that in the preceding months he

had held a bunch of yellow flowers and at Christmas, a Santa Claus doll. In 2009 he held a toy rabbit linking him with

another literary person, Beatrix Potter.

The frivolity is a new development. When the statue was first proposed the church

Vestry noted that no statue had yet been erected of “one of the greatest poets of this or any other country ...” and

looking to “... a suitable public memorial

to mark local appreciation of his fame.”

The

statue was made by Horace Montford.

Details of his life are hard to find.

He was the father of Paul Raphael Montford (1868 - 1938), also a

sculptor, who travelled to Australia and made many well known statues in

Melbourne. Maurice Grant wrote that Horace was “equally known

as (Paul), he was of equal merit and equal industry showing more than 50 works

in the galleries from 1860 to early in the XXth century”. These works included some subjects taken from

Milton. At the time of his Milton

commission he was best known for a statue of Charles Darwin at Shrewsbury.

The

statue originally stood on a pedestal designed by E. A. Rickards with reliefs

illustrating some of Milton’s works. The bombing raid which devastated the

church knocked the statue off this pedestal and it has never been

restored. Milton’s right hand was

damaged and has since been replaced in fibre glass.

The

Plinth remains outside the church in a much deteriorated condition.

All

attempts to restore the statue to the plinth or a replacement have failed, apparently

due to an arcane dispute about the ownership of the statue and plinth.

As

damage to the church and statue occurred in the first Nazi raid on the City of

London, Milton’s fall was reported around the world.

In

Australia, Ralph E Robson of Mosman wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald:

Sir-The bombing of

this statue in London makes one wonder whether Hitler was contemplating revenge

on the author of “Paradise Lost", realising that London (his coveted

Paradise) can never be captured and is therefore lost to him. Hitler will do

well to ponder over the words of the blind poet who said:-

When God wants a hard thing done in the world.

He tells it to His Englishmen

A prophetic

utterance now in course of fulfilment.

I am. etc..

It’s not uncommon for bursts of

enthusiasm for the famous dead to result in the erection of statues and

memorials; sometimes long after the death of their subject. In this case, however, Milton’s own opinion

was not consulted. He wrote of

Shakespeare:

What needs my

Shakespeare for his honored bones

To labor of an

age in piled stones,

Or that his

hallowed relics should be hid

Dear son of

memory, great heir of fame,

What need'st thou

such weak witness of thy name?

Thou in our

wonder and astonishment

Hast built

thyself a livelong monument.

For, whilst, to

the shame of slow-endeavouring art,

Then thou our

fancy of itself bereaving,

Dost make us

marble with too much conceiving,

And so sepúlchred

in such pomp dost lie

That kings for

such a tomb would wish to die.

|

A fascinating Elizabethan, EdwardAlleyn (1566–1626) is commemorated in a modern stained glass window in St. Giles.

The window was made by JohnLawson (1932 – 2009) of Goddard and Gibbs.

Alleyn was an actor

who at 17 was performing with a touring company the

Earl of Worcester's Men. By his mid

twenties, he was performing with Lord Strange’s men at the Rose theatre. He then became leader of the Admiral's Men and

is best known for his performances in Marlowe’s plays. In, The

World of Christopher Marlowe, David Riggs writes that “...in performing the

role of Tamburlaine, Edward Alleyn became the first matinee idol in English

Drama.”

He became part owner of The Rose theatre, and later

built The Curtain, situated in the

parish of St. Giles. By about 1597 had ceased to act on the stage

altogether. Together with his father in

law Philip Houslow he pursued these and other investments.

In particular, Alleyn and Henslowe attempted, at

first without success, to gain the official post of master of the bears, bulls,

and mastiff dogs. This carried with it a

lucrative monopoly in animal baiting. In

1604 they purchased the patent and between them held the position for many

years. They became proprietors of The

Beargarden, a long standing arena on Bankside near the Rose and Globe theatres. It is

said that Alleyn himself took part in the baiting of bears.

The past is indeed another country. These cruel and disgusting spectacles were popular

with the same crowd who first saw Shakespeare’s plays.

From this and other investments, Alleyn accumulated

significant wealth. He purchased Dulwich

Manor which included large areas of land in and around Dulwich. His philanthropy included the foundation

of College

of God's Gift at Dulwich, gifts to

the poor in the parish of St. Giles and bequests to enable the building of ten

almshouses in the parishes of St Saviour's Southwark (now Southwark Cathedral )

and St Botolph without Bishopsgate.

The design of the window incorporates a

portrait of Alleyn taken from one by an unknown artist held by the Dulwich

Picture Gallery. Above is the family

coat of arms in which I think I can recognise a chevron

between three cinquefoils gules. In his

hands we see a representation of the alms houses. The Fortune theatre is depicted to his right

and to his left, the church of St Luke Old Street.

On its face, this is peculiar as St Luke’s Old

Street did not exist in Alleyn’s day. It

was built in 1733 to relieve St. Giles but later fell into disrepair and was

deconsecrated. It has now been

redeveloped as a music centre by the London Symphony Orchestra. The distinctive tower of St. Luke’s was

designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The LSO attributes the whole building to

him. Some of the furnishings of St.

Luke’s, including the organ case, were used to replace those destroyed in the

bombing of St. Giles. It seems that

almshouses founded by Alleyn and destroyed in the war were administered by the

St. Luke’s parish council, and this provides the reason for the appearance of that

church in the window.

I wonder, however, how closely the people

who commissioned and designed the window looked at the history of St. Luke’s

and of The Fortune. The Fortune was built in 1600 over the

objection of the Parish of St. Giles which prevented work on the building

proceeding until the Parish was defeated by a warrant issued by the Privy

Council at the behest of Alleyn and the patron of his troupe the Earl of Nottingham, the Lord

Admiral. The building and licensing of

theatres was a contentious activity at the time not the least because theatres

of any kind were opposed by the puritan element.

The

machinations of Edward Alleyn would be a fascinating study: his acts of charity

in the Parish were not entirely disinterested.

When seeking the warrant of the Privy Council for the construction of

The Fortune,”by offering ‘to give a very

liberal portion of money weekly’ towards the relief of ‘the poor in the parish

of St. Giles,’ he persuaded many of the inhabitants to sign a document

addressed to the Privy Council, in which they not only gave their full consent

to the erection of the playhouse, but actually urged ‘that the same might

proceed.’"

The

link between his philanthropy and The Fortune is preserved in the window.

The

original Fortune theatre was destroyed by fire in December 1621 and replaced by

a new building. Although no image of the original theatre

has been found, detailed building plans survive which have permitted the

construction of modern replicas and models.

I

was happy to find that one of these is in the grounds of Waseda University

Tokyo. The Tsubuchi Theatre Museum is named for Dr. Shoyo

Tsubouchi (1859 –1935) and was

opened in 1928 to mark both his seventieth birthday and the completion of his

translation of the complete works of Shakespeare into Japanese.

I

always seem to get lost in Waseda. This

time I searched “from ... to “directions from Waseda station and, not having a

printer, attempted to memorise the map.

I headed away from the station in what proved to be the wrong

direction. I blame google maps which mischievously

inverted the map when plotting the route.

After going too far and finding nothing, I sought help from an elderly

couple waiting for customers in one of those shops selling mysterious

ironmongery. The husband kindly came

with me back into the street and waving in the direction I had come, told me that

I must retrace my steps. I did, but

still having a faint memory of the inverted map it took me some time to reach

the theatre museum.

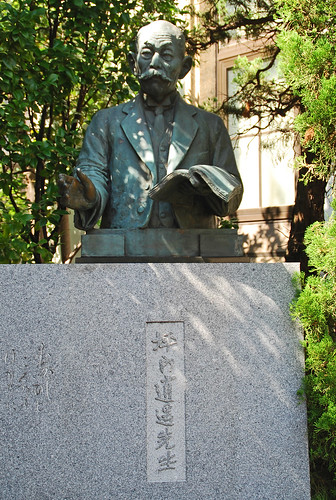

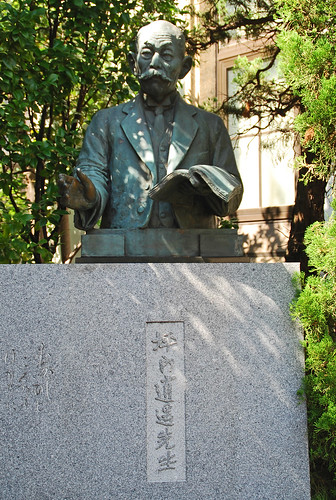

A

portrait bust of Dr. Tsubouchi stands outside the museum. I wish I was more refined, but I still

experience surprise when I come across someone who challenges national stereotypes.

As well as translating the whole of Shakespeare, Dr Tsubouchi was a Chickamatstu scholar, directed productions of contemporary European drama including Ibsen, and founded the Literature Department at what is now Waseda University.

As well as translating the whole of Shakespeare, Dr Tsubouchi was a Chickamatstu scholar, directed productions of contemporary European drama including Ibsen, and founded the Literature Department at what is now Waseda University.

The

building itself is a cutaway version of the original with a covered stage but

no rear section or galleries.

Inside

there are rooms devoted to Shakespeare and the various genres of Japanese theatre

as well as film. I found the most

fascinating room to be the Shoyo Memorial Room, where Dr. Tsubouchi worked

during his lifetime and which contains memorabilia of his life and work. He was born in the year of the sheep and

there are depictions of sheep on the ceiling.

There is also a collection of model sheep on display: “It is said that

he grew very fond of sheep as symbols of ‘bookworms’ who like to read books,

linking to sheep the paper eaters”. Near

the sheep is a collection of small busts of Shakespeare and similar items from

the souvenir shops

of Stratford-upon-Avon.

* to reach the picture gallery from this link click on "heritage" on the top bar, then "archive material" then "we have a page..." It does not seem possible to link to the pictures directly.

of Stratford-upon-Avon.

* to reach the picture gallery from this link click on "heritage" on the top bar, then "archive material" then "we have a page..." It does not seem possible to link to the pictures directly.

Most

of the information about The Fortune (and the quote) comes from: Shakespearean

Playhouses A History of English Theatres from the Beginnings to the Restoration

by Joseph Quincy Adams an excellent and thorough account of Elizabethan and

Jacobean theatres which is available at the Gutenberg project and as a free

Kindle book.