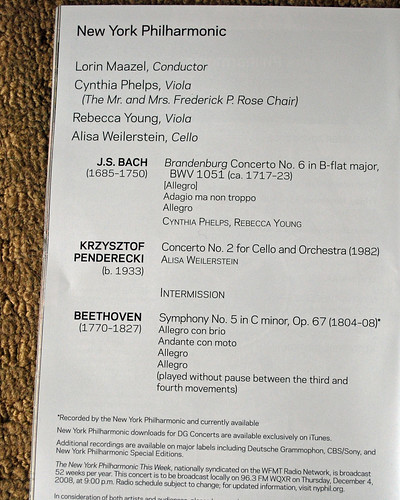

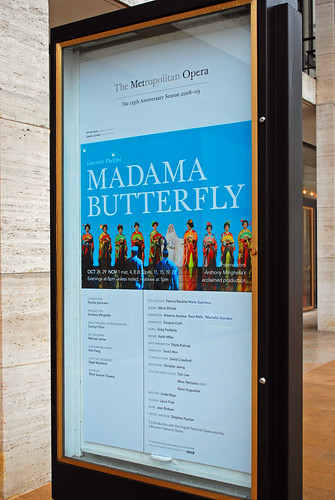

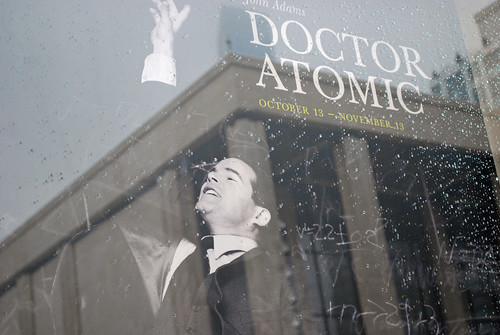

J. Robert Oppenheimer the subject of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic, which I saw at the Met earlier in November, attended school at the Society for Ethical Culture, so it was appropriate that the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center was performing there during the renovations of Alice Tully Hall. I heard one of a program of four concerts given under the title “Night Fantasies”. It was lucky I didn’t chose the first concert on November 20 as this was cancelled following a small fire in the basement. I walked past that night and saw the fire trucks and concert goers milling about, but didn’t learn the concert had been cancelled and rescheduled until an announcement at the beginning of the concert on November 21. They had to extend the hire of some percussion which was on the stage on Friday but not used.

The seating in the hall is in two levels in a semi circular formation around a low stage.

Above the stage is an inscription:

"The Place Where People Meet to Seek the Highest is Holy Ground"

The acoustics were good as well. The program ingeniously included three fairly short works with a numerous short movements. The principal artists were the Pacifica String Quartet, which I was interested to hear as I recently purchased their CD of two of the string quartets of Eliot Carter, which I plan to use, if time permits, to see if listening to Carter as a stream of consciousness, (an idea discussed by David Robertson in his recent Stuart Challenger lecture) helps at all with this difficult music.

The performance I heard on 21 November demonstrated the quartet’s great commitment to and understanding of contemporary music.

The program opened with a performance of Gyorgy Ligeti’s String Quartet No. 1 “Metamorphoses nocturnes”. My interest in Ligeti’s music was enlivened this year by a performance of his horn trio at the AFCM Townsville, but a CD I bought of this trio disappointed.

The String Quartet No.1 is about 20 minutes long and divided into 12 movements which are very short accordingly. They are fragments really. Each is different; and some of them had the same intense rhythmic drive I admired in the horn trio.

Next was another work of 20 minutes duration: Black Angels (Thirteen Images from the Dark Land) for Electric String Quartet by George Crumb.

My only previous encounter with Crumb’s music was a performance of Vox Balaenae (Voice of the Whale) (1971), for electric flute, electric cello, and amplified piano at the AFCM a couple of years ago. The musicians wore masks for that (I don’t know if the masks are required by the score). It was notable for the excellent whale song imitations of the amplified cello which were quite moving (suggesting that Alan Hovhaness went to unnecessary trouble in incorporating recordings of real whale song in And God Created Great Whales).

If I count correctly there are 13 movements in this work. I have seen the Kronos Quartet play with electronics attached to their instruments but in this concert the amplification seemed to be done by individual microphones on stands. There was more to it than amplification however. The members of the quartet also played tuned drinking glasses set up on stands behind them, struck gongs and sang or vocalised. There was also an intriguing passage in which the players bowed the neck of their instruments, yielding an early music viol effect.

13 movements in 20 minutes with such a variety of effects was certainly interesting if hectic, and I haven’t mentioned the references to “Death and the Maiden” and other works which I was unable to hear. I would describe the piece as interesting and fun but the composer had much deeper thoughts. “The numerous quasi – programmatic allusions in the work are therefore symbolic, although the essential polarity – God versus Devil – implies more than a purely metaphysical reality” is just part of a long note by the composer. Fortunately the music is not as ponderous.

After intermission the quartet was joined by soprano Claron Mc Fadden in a performance of Lyric Suite for String Quartet with Soprano by Alban Berg, which was also full of interest but which I will need to hear again before being able to comment.

The programmer recognised that there can be too much of a good thing, I think, and abandoned stark modernism to conclude the concert with the charming Chanson perpetuelle for Soprano and Piano ( Gilbert Kalish) Quartet by Ernest Chausson.

(Revised 6 September 2009)

I visited Brisbane for a commercial purpose but went down to the Queensland Art Gallery as well, mainly to see the exhibition Mountains and Streams, since I am taking an interest in Chinese Art at the moment by attending the lectures Literature and Legend at the Sydney gallery. The lectures on Chinese Art are part of series which moves on to Japanese Art later. I thought the Chinese lectures would be a useful prelude to the Japanese ones but despite their variable quality I found much interested in the history, art, and literature discussed. I found I had seen Mountains and Streams previously at the NGV in Melbourne where it originated but had almost no memory of it, attributable, I think, to my complete ignorance of Chinese art when I first saw it. So I saw it again with a little more insight.

But the highlight of my visit to the Queensland gallery was my discovery of Yayoi Kusama, a Japanese artist whose installation, Narcissus Garden, is a striking feature of the gallery itself. The Queensland gallery is new. I found it to be a splendid large and open space very well designed for the display of painting and sculpture.

The installation by Yayoi Kusama is a version of a work which she first showed in 1966 at the Venice Biennale; or rather outside it, since she had not been invited. It was a very effective action and brought attention not only to herself but also to the way in which official displays of modern and inventive art soon become as ossified and bureaucratic as anything else. At the Biennale Kusama first offered the individual mirror balls for sale at $2. When she was somehow prohibited from doing this she gave out leaflets praising her own work.

Other versions of this work have appeared in the Serpentine in London and the small boat lake in Central Park, NYC. From photographs, it seems that the mirror balls were set out on the grass when they first appeared at Venice but subsequently floating in water. The essence of the installation is the reflective balls themselves. It looks from photographs as if their surroundings at Brisbane have changed a little from time to time; and in other places they seem to be out of reach and more clumped together in the waters and lakes in which they are floating.

In Brisbane the accumulation of balls looks simple and elegant and attracts attention by the constant movement helped along by the notices calling for them to be touched gently.

I find that Kusama has been an influential artist for 50 years. She was born in Matsumoto in 1929 and traveled from Japan to the USA in 1958. She was soon in New York where she was active in painting, sculpture and the organization of happenings for some years. She was therefore involved in making installations and other similar works when the concept was truly innovative and she was able to work with originality and flair. It may still be possible to do this, but the passage of time has made so many of such things seem mundane and derivative.

Although not apparent in Narcissus Garden, Kusama has described her work as emerging from her mental illness: she says has had hallucinations since she was a child. She also says that her ability to produce artistic works is a therapy for her.

Kusama often appears in photographs of her work. In a picture of the installation at Venice she is seen lying on the ground amongst the metallic balls in a red jumpsuit. In more recent photographs she poses staring intently at the camera. I wonder about the border between mental illness and self promotion.

Or could it be a characteristic of Japanese artists who move to the west. I am reminded of the self portraits of Fujita staring languidly from the picture; and of his self promotional antics in Paris in the 1920s.

And I can now add Masami Teraoka whom I discovered in Melbourne even more recently. His MacDonald's Hamburgers Invading Japan / self portrait shows the same trait:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Teraokaselfportrait.jpg

And so it was that in late May 2008, I made my way to Matsumoto, taking the super wide Shinano via Tsumago/Nagiso. I enjoyed my brief visit to Matsumoto. I missed a special retrospective exhibition of Kusama's work by only a week or so. However, as Matsumoto is her home town, the Matsumoto City Museum of Art maintains a permanent exhibition of her work. In fact, her Visionary Flowers (2002) dominates the front of the building; I imagine it was made for the site as the museum opened in that year.