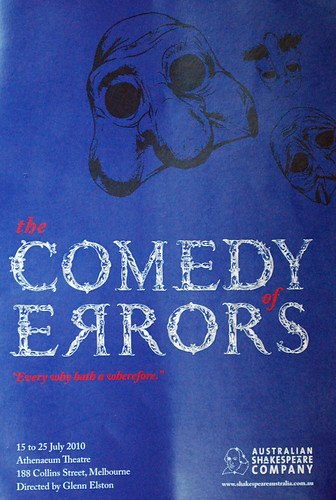

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

This all began in Townsville in August. I was there for the Australian Festival of Chamber Music and after hearing a concert which included various pieces by Argentinean composer Astor Piazzolla it was only to be expected that I would find a message from Argentina on my laptop, and there it was:

Hi !

I was wondering if you have more pictures of this:

"Art Nouveau fountain by C.B. Birch surmounted with a bronze statue of a young girl with a heron and reeds and frogs at the base"

That´s an awesome fountain and it would be great if you could upload more images.

Thank you!

Esteban

Esteban was referring to this photo which I had taken in the Sydney Botanical Gardens the year before:

The description attached to the photo came from

The Royal Botanical Gardens website.

I found that Esteban was from Córdoba, Argentina; and provoked by his interest decided to re visit the statue on my return to Sydney.

The fountain, said to be one of the last remaining drinking fountains in Sydney, was erected as a memorial to the businessman and politician Lewis Wolfe Levy, who was born in London in 1815 and came to Australia in 1840. He had an active and successful business career, was twice elected to the Legislative Assembly and was later appointed to the Legislative Council. He died in 1885: according to the

Australian Dictionary of Biography,

"Although self-made, plain spoken and occasionally short tempered, he was widely respected and sincerely mourned".

There is a more detailed description of the fountain in the excellent

Poetry of Place by Edwin Wilson, which catalogues and describes all of the statues in the gardens and the Domain. The bronze statue of a water nymph with a heron and surrounding reeds and frogs is the work of Charles Bell Birch, the English sculptor who is discussed here. The statue was erected in 1889 having been cast at a foundry at Thames Ditton in England.

I don't think "

Art Nouveau" is a misdescription of the style: it looks that way to me, but it would make Birch a very early exponent of Nouveau. The

Maison de l'Art Nouveau in Paris opened in 1895,

and the movement itself is given the dates 1890 - 1905. The Arts and Crafts movement in England is often cited as a source of Art Nouveau and Birch would surely have been exposed to the movement, but his other work and the little I have discovered about him do not suggest a relationship.

I have found that Birch is a neglected artist in the neglected genre of Victorian sculpture. From one point of view the lack of interest in this field is hard to understand. The cities of Britain, and the old Empire, including Australia, are decorated with statues and sculptures from the nineteenth century made by artists in whom little interest remains. The works are seen by millions of people every day but the artists are unknown.

There are a few references to Charles Birch in more general books and on the web, but no biography I can locate and no article in wikipedia as yet. There is, however, an article in the Dictionary of National Biography.

He was born in Brixton in 1832, the son of Jonathan Birch, an author with the unrealised ambition of becoming a sculptor himself. While still a youth, Charles Birch travelled to Germany where he studied at Kurfürstliche Akademie der Künste and with the German sculptors Ludwig Wichmann and Christian Rauch. It is

suggested that:

" his style was more or less set by his training in Berlin, with what has been described as 'a naturalistic veneer upon a classical foundation'." I would need to know much more about the German style of the period to assess this view, but the works which I have seen don't seem to embody any one particular style.

Birch returned to Britain in 1852, and entered the Royal Academy Schools. Then in 1859 he became principal assistant to John Henry Foley and remained in that position until Foley's death in 1874.

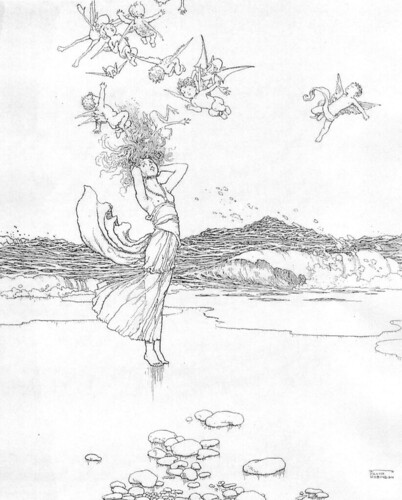

He had his first great success in 1864 when the Art Union of London awarded him a premium (meaning, I think, a prize for acquisition) of 600 pounds for "A Wood Nymph", which was shown in Vienna, Philadelphia and Paris.

There is an image of this work here: although a nymph, this one seems quite different from the water nymph seen in the Levy fountain.

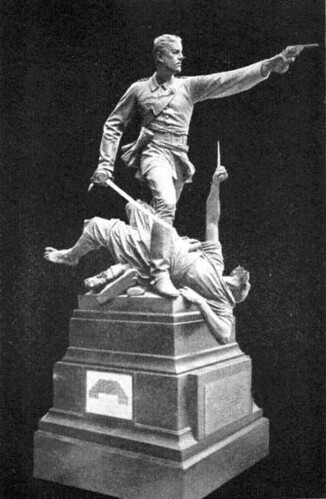

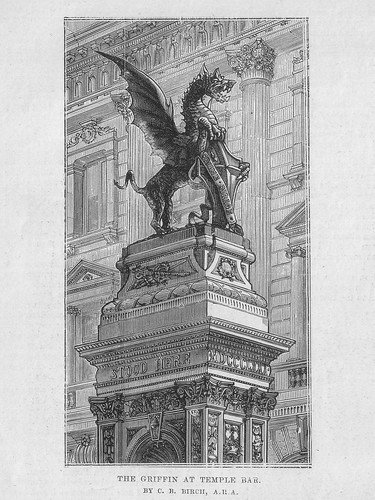

Birch sculpted " realistic and vigorous " or Boy's Own - depending on your approach- military sculptures. He made The Last Call in 1879:

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

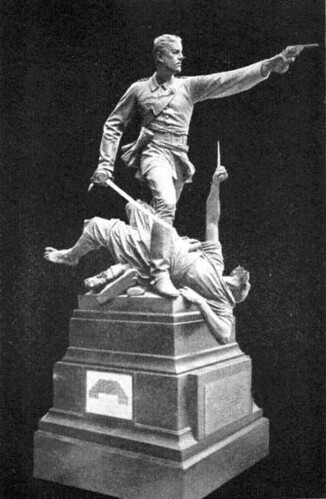

and Walter Hamilton VC "

striding over an Afghan threatening him with a knife " in bronze-painted plaster in 1880.

These works have a recognisable style of their own, which looks to me quite different from either nymph.

The success of Hamilton VC resulted in Birch being elected an associate of the Royal Academy in April of 1880.

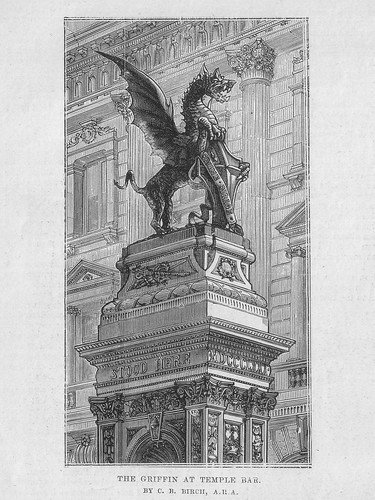

Birch was at the height of his fame in that year, in which, what must be his most often seen work, the griffin on the Temple Bar Memorial in London was erected.

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

from The London Illustrated News, 21 October 1893

The Temple Bar Memorial which replaced the old Temple Bar was a controversial project at the time. The Temple Bar itself was removed because it had become an obstruction to traffic, but the new memorial was seen as another, if lesser, obstruction in itself. The DNB calls Birch's sculpture " the unfortunate bronze griffin", but I would like to think that at least some of the criticism of it which is reported confuses opposition to the structure itself with a dislike of the griffin.

Phillip Ward Jackson in

Public Sculpture of The City of London notes that when the memorial was opened by Prince Leopold in September 1880, with Birch in attendance,

The Times reported that

"...a crowd stationed within the new Law Courts groaned throughout the brief ceremony".

Ward Jackson also records that a critic in the

Builder commended the "vigour and power" of the griffin while the

Architect said that " the artistic courage and strength of will manifested in this magnificently ungainly object are prodigious ". There was no unanimity however:

Building News stated:

"...Let the First Commissioner of Works seize the opportunity and draw (Queen Victoria's) attention to that wretched object the Griffin. If Her Majesty does not counsel its immediate removal, she has lost the unerring perception of truth and beauty which have distinguished her reign".

And Darke's The Monument Guide to England reports that the griffin has been likened to

" an animated corkscrew ".

But it has guarded the entrance to the city for almost 130 years.

Charles Birch is often said to be an exponent of The New Sculpture, understood to be a movement towards greater naturalism in later Victorian sculpture. The critic Edmond Gosse used the term in articles written in the 1890's. Frederick Leighton's

Athlete Wrestling with a Python of 1877 is seen as the key work in the movement.

Two copies of this work are presently displayed in the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Not far from them is Charles Birch's

Retaliation made in 1888 and exhibited at the Sydney International Exhibition in 1879 where it won the award of "First Degree of Merit Special".

It can be seen in this photograph from the Art Galley archives taken in 1881:

And again in 1885 in the new gallery:

It didn't remain in fashion however and in 1958, it was sold to the Botanical Gardens, where it was placed in the pathway through the Palm Grove. It was not undisturbed: in 1961 a truck collided with the statue requiring repairs to its marble base. Then in about 1977, the Art Gallery had second thoughts and arranged to take it back as a swap for

The Satyr by Frank Lynch now in the Gardens near the Opera House gates.

It is quite likely that

Retaliation was influenced by the

Athlete Wrestling but as it was completed only a year later, it would not be possible to say this with certainty without more information. It is a work of high drama, the naked shepherd, (note the crook), appears to have wrung the neck of the bird of prey responsible for the death of the lamb lying at his feet.

Perhaps it was the success of this work which led to Birch's commission to make the Levy fountain. But if he drew the inspiration for

Retribution from Leighton, what was the source of the bronze statue of a young girl with a heron and reeds and frogs at the base on the Levy Memorial Fountain ?

Birch died in 1893. A full page tribute was published in

The London Illustrated News including the images reproduced above. The article was as follows:

THE LATE MR. C. B. BIRCH, A.R.A.

The death of Mr. Charles Bell Birch, the well-known sculptor, removes an interesting and prominent figure from the world of art. Mr. Birch died on Monday Oct. 1, at the age of sixty-one, having been born in Brixton in 1832. For many years he was a student of the Berlin Royal Academy.

It was in Berlin, in 1852, that he produced his first important work, a bust of the late Earl of Westmorland, at that time Ambassador to Prussia. On his return to England Mr. Birch entered the studio of the late Mr. Foley R.A., where for ten years he acted as principal assistant ; in 1864 he was the successful competitor at an Art Union competition, where his subject, " The Wood Nymph," carried -off the prize of £600. For many years Mr. Birch was acting as a wood-engraver, and much of his work may be seen in the pages of this Journal, as well as in other publications. His equestrian group, " The Last Call," exhibited at the Royal Academy, which is here reproduced, was the proximate cause of his election to the Associateship of the Royal Academy in 1880. It is, perhaps, by the work which we reproduce here, the famous Griffin, which looks down upon us from the site of Temple Bar, that Mr. Birch is most widely known to the public, although a mere list of his statues -would make a formidable catalogue. At a later period he devoted himself to producing statues for public buildings in this country and the colonies, and many of these were marked by considerable vigour and massiveness. In his more imaginative work amongst which must be included the silver statuettes and race cups for which he received frequent commissions, he allowed his fancy fuller play, but as a rule his work suffered from the constant pressure under which it was produced.

Towards the end of his life, Birch made a statue of Queen Victoria, of which a number of casts were made. The first was made for Udaipur in India and was erected there in 1889. After Birch's death a cast of it was erected on the northern approach to Blackfriars Bridge in London. It was unveiled by the Queen's cousin, the Duke of Cambridge, on 21 July 1896. The duke regretted the sculptor had not survived to see his work erected there.

I looked for it in November 2009, but did not see it. I assumed it had been moved to a place of safety during the renovation works being done in and around Blackfriars Station.

Another example was given to the City of Adelaide by Sir Edwin Smith MLC and erected there in 1894. It stands in Victoria Square where I saw it in March 2010.

*************

Posted 12 February 2010

Amended 23 February 2010 to add illustrations and quotation from The London Illustrated News

Amended 10 March 2010 to add Queen Victoria in Adelaide

![08Mage-poster[1]](http://farm5.static.flickr.com/4079/4870322387_ce2265dcf9.jpg)